22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome | Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of 22q11.2 deletion?

Children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome can have a wide range of signs and symptoms, with differing degrees of severity. Some babies show signs of the condition at birth and others are diagnosed in the first few years of life.

Common symptoms include:

- heart problems

- low muscular tone

- speech difficulties

- middle ear infections or hearing loss

- vision problems

- feeding problems

- frequent infections

- learning disorders, especially with visual materials

- developmental delays

- communication and social interaction problems

- psychiatric issues

Facial features may include:

- small ears with squared upper ear

- hooded eyelids

- cleft palate

- asymmetric facial appearance when crying

- small mouth, chin, and side areas of the nose tip

What is the cause of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

This condition is caused by a missing a part of chromosome 22. The specific area of the chromosome that is missing is 22q11.2. The exact size and location of the missing chromosome can vary, and this is thought to explain some of the variability in medical problems associated with the disorder. About 10 to 15 percent of cases are inherited. A parent with 22q11.2 deletion has a 50 percent chance of passing it on to each of their children. It’s estimated that about 1 in 4,000 children are born with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, however it may actually be more common since mild cases may go undiagnosed. In some cases a deletion is not present but there is a change in a gene called TBX1.

22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome | Diagnosis & Treatments

How is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome diagnosed?

In some cases, particularly if your child has a heart problem or a cleft palate, diagnosis will be made in infancy. In other cases, diagnosis happens later in childhood. If your child’s doctor suspects 22q11.2 deletion syndrome based on symptoms, he or she will refer you to a geneticist who may suggest a genetic test to diagnose the condition.

The doctor may also recommend one or more of following tests to rule out other conditions or to or check for specific problems associated with 22q11 deletion:

- echocardiogram (cardiac ultrasound)

- kidney ultrasound

- x-rays

- blood tests

If your child’s medical history and physical exam are very suggestive of 22q11.2 deletion but the deletion testing is normal, your doctor may suggest TBX1 gene sequencing. TBX1 is a gene within the 22q11.2 deleted region and there are rare examples of individuals with mutations in this gene who have many of the features of 22q11.2 deletion.

How we treat 22q11.2 deletion syndrome

Boston Children’s Hospital provides a wide range of diagnostic, treatment, consultation, and advocacy services for children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Our experts are experienced in caring for children who have 22q11.2 deletion. We advance care through early diagnosis and evidence-based protocols geared to specific disorders such as 22q11.2 deletion, in order to maximize the quality of children's lives. Although there is no cure for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, a range of options are available to address health problems related to the syndrome. For this reason, the first step in treatment is a careful screening to check for underlying medical problems.

Common problems with 22q11.2 deletion that may need treatment include:

- Heart defects: Children born with heart defects may need surgery to correct the condition.

- Cleft palate: Some children may need surgery to repair the opening in their palate.

- Feeding difficulties: Children who have severe feeding difficulties may need tube feedings to get proper nutrition, other children have issues with reflux or discoordinated feeding that benefit from medication and/or feeding therapy.

- Low calcium: Children may need to take calcium supplements as well as vitamin D to help absorb the calcium.

- Immune deficiency: generally requires no specific intervention except treating infections aggressively. Rarely, prophylactic antibiotics, IVIG therapy, or thymic transplantation are required.

- Developmental, psychological, and learning difficulties: Early intervention services may be recommended to help children reach developmental milestones. As they grow, children with 22q11.2 deletion may also benefit from special education services, physical and occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Children and young adults are at an increased risk for anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric complications that benefit from early identification and treatment.

Problem-focused programs

At Boston Children’s Hospital, we have a number of unique programs to comprehensively assess and treat the many medical challenges a child with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome may have. All programs will not be needed by every child or at every stage of life. However, our comprehensive team-based approach will make sure your child has access to any or all services that he or she may benefit from.

Congenital heart defects are present in the majority of children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The most common congenital heart defects are called conotruncal lesions and include interrupted aortic arch, truncus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, and ventricular septal defects are also frequently diagnosed in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, as can other congenital heart defects. Congenital heart defects may be detected prior to birth or after delivery. An echocardiogram, or ultrasound of the heart, is used to evaluate all of the structures of the heart and detect any abnormalities. Congenital heart defects often require management soon after birth as they can cause difficulty with circulation, breathing, and/or growth. Often children are treated first with medications to ensure safe circulation, followed by possible surgical or catheter intervention depending on the particular defect and how the child is doing. Children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome who have congenital heart disease require lifelong cardiac care. Further procedures, including cardiac catheterization and surgery, may be needed in childhood and .

Children with congenital heart disease can face challenges in other aspects of life, such as academics and social functioning. The Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Program at Boston Children’s Hospital is formed by a team of specialists in Cardiology, Cardiac Surgery, Developmental Medicine, Genetics, Neurology, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Radiology to support the needs of children with congenital heart disease beyond their cardiac care. By collaborating with families, schools, and other providers in the community, each child is provided individualized recommendations to optimize functioning and quality of life.

The Cardiovascular Genetics Program provides innovative clinical care, education, and research. Patients and families have access to the latest diagnostic modalities and innovative therapies in cardiology, genetics, and related subspecialties. The clinic provides family focused care, addressing the full range of cardiac and genetic services, from the prenatal period to adulthood. Patients are evaluated annually to be sure all aspects of care that are specific to 22q11.2 deletion are being monitored or treated.

Some children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have an opening in the roof of their mouth, called a cleft palate. A cleft palate can affect speech, hearing, and feeding, and often special bottles or even a feeding tube may be needed during infancy. If your child is healthy enough, a cleft palate is usually corrected by surgery between 9 and 12 months of age. Cleft palate surgery may be delayed when other issues, like heart problems, take precedence.

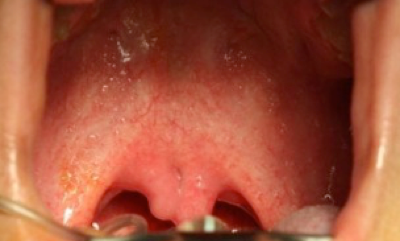

Other children will not have an obvious opening in the roof of the mouth, but will have a split uvula and the separation of the muscles in the palate (Figure 1). This is called a submucous cleft palate and can cause the same feeding, speech, and hearing problems as a cleft palate. Because there is not an obvious opening in the roof of the mouth, submucous cleft palate is often diagnosed later in childhood when children have difficulty with speech. Not every submucous cleft palate needs an operation — surgery is typically reserved only for those children where speech and/or feeding is affected.

Children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome may have a variety of developmental delays and behavioral challenges, some unique to 22q11.2 deletion, and others that are more common. The Developmental Medicine Center can help provide comprehensive developmental and behavioral evaluations and design treatment plans to optimize your child’s potential and quality of life.

Children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome may behavioral and emotional challenges and some may be diagnosed with conditions such as ADHD, OCD, or anxiety. If concerns arise about your child’s mood or behavior, a comprehensive neuropsychiatric evaluation may be recommended. Early intervention can help maximize your child’s quality of life.

Infants and children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome may have difficulties with feeding and swallowing. These may be related to or separate from their congenital heart defects or palatal abnormalities. Some children with severe feeding or swallowing difficulties may require tube feeds to help them grow.

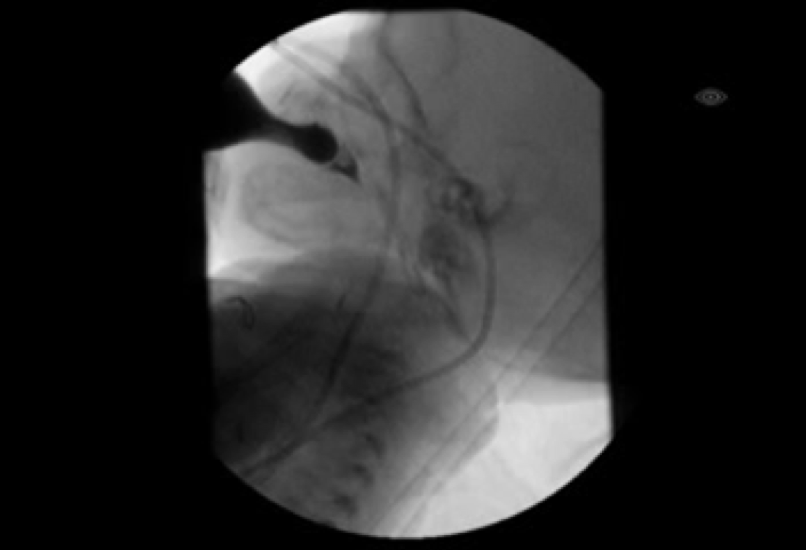

Infants may have a weak suck, which can lead to prolonged feedings or poor weight gain. Some may require special bottles or nipples to help them drink enough. They may also have liquid come out of their nose when feeding or spitting up, which can be uncomfortable but is not dangerous. Infants may have difficulty coordinating their sucking with swallowing and breathing, which can lead to liquid entering the lungs when swallowing, called aspiration. Older children can also have signs of aspiration, such as coughing, choking, and congestion when drinking or recurrent respiratory infections. If aspiration is suspected, a Modified Barium Swallow study will likely be recommended (Figure 2). This is a dynamic x-ray study that assesses your child’s swallow function while they eat and drink.

Some children may also have difficulty with transitioning to solid foods and cup or straw drinking as they get older. These difficulties are often a result of low muscle tone or palatal differences. Some children gag with pieces of food or spit them out and may require assistance in learning to chew foods completely. Your child may also have trouble generating enough suction to drink from a straw. Feeding therapy can often help with improving oral motor skills for chewing and cup or straw drinking.

Children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome can have many different challenges as they begin to understand language and produce speech. Some of these challenges are related to developmental delays and may improve with speech therapy. Other challenges are related to structural differences. In addition to cleft palate and submucous cleft palate, speech production can be impacted by poor muscle tone and having a wider and deeper space in the back of the throat that allows too much air to come out of the nose. This is called “velopharyngeal insufficiency” and often requires surgery. Periodic comprehensive speech and language assessment throughout childhood is important in identifying the developmental and structural differences that impact communication, and determining appropriate interventions.

If velopharyngeal insufficiency is suspected, your child may be referred to the Voice and Velopharyngeal Dysfunction Program. In a multi-disciplinary setting, your child will undergo a detailed speech evaluation and will be examined by an otolaryngologist and a plastic surgeon. To help identify the cause of your child’s speech problem and to determine what treatment will be most effective, an otolaryngologist may use a small camera to look into the back of your child’s nose and throat. This exam helps to determine if a submucosal cleft palate exists, and also evaluates for a possible vocal cord web, which is another condition seen more frequently in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The “Your Visit” section of the website has helpful tips to prepare your child for this evaluation.

Figures

|

Figure 1. Submucous cleft palate In a submucous cleft palate, there is not a gap or hole in the roof of the mouth. |

|

|

Figure 2a. Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) study How a MBS is performed A MBS is a test used to look for aspiration. Fluoroscopy, similar to an x-ray, |

|

| Figure 2b. What an MBS looks for

During the MBS, the liquid a child drinks includes a special dye that can be seen on x-ray. We watch as the dye moves from the bottle or cup, though the mouth and throat, and can see if it is entering the child’s airway (aspiration) while he or she feeds (photo courtesy of Katie Engstler, SLP). |

|