Syndactyly | Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of syndactyly?

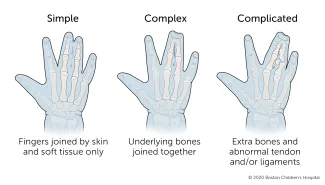

Symptoms of syndactyly differ depending on the type your child has. There are three types of syndactyly: Simple, complex, and complicated.

- Simple syndactyly means that the fingers are joined by skin and soft tissue only.

- Complex syndactyly means that the underlying bones are also joined together.

- Complicated syndactyly means that there are extra bones, and the tendons and ligaments have developed abnormally.

What causes syndactyly?

During pregnancy, a baby’s hands form in the shape of a paddle and later split into separate fingers. This happens very early, around the sixth to eighth week of pregnancy. Syndactyly happens if two or more fingers do not separate during this time.

Syndactyly often runs in families. About 10 to 40 percent of children with syndactyly inherit the condition from a parent. In some cases, the condition is part of genetic syndrome, such as Poland syndrome or Apert syndrome.

Syndactyly | Diagnosis & Treatments

How is syndactyly diagnosed?

Syndactyly is often diagnosed at birth. Sometimes it is detected even earlier, on a prenatal ultrasound.

Your baby’s doctor may use X-rays to assess the underlying structure of your baby’s fingers and determine a course of treatment. They may also evaluate your baby’s arms, shoulders, chest, feet, head, and face to look for signs of other abnormalities.

How is syndactyly treated?

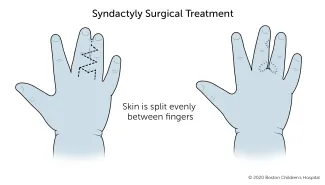

Syndactyly is treated with surgery to separate the joined fingers. Your child will probably have this operation when they are between 1 and 2 years old.

During surgery, the skin is split evenly between the two fingers. Your child may need a skin graft or a skin substitute to cover the newly separated fingers. Skin grafts are usually taken from the elbow or wrist crease to minimize scarring.

To avoid possible complications, only one side of a web space is separated at a time. If your child has several fingers involved, they will need more than one surgery.

Syndactyly in Apert syndrome

Children with Apert syndrome typically experience syndactyly. There are three main types of syndactyly in Apert syndrome: Type I (spade hand), Type II (mitten hand), and Type III (rosebud hand).

What happens after surgery?

Your child will wear a cast or bandage covering their hand, lower arm, and elbow for two to three weeks. This will keep their hand still and protect the healing skin. Once the cast comes off, they will wear a splint to keep the fingers apart for six weeks.

Your child’s doctor may recommend occupational therapy to reduce scarring, manage stiffness and swelling, and improve function.

Some children who have had surgery experience “web creep” as they grow. This happens when scar tissue grows in the space between the fingers, making it look like syndactyly is coming back. Your child may need a second surgery if this happens. Web creep is more common when the digits are separated before age 1.

Your child should have regular follow-up visits with their care team to make sure their hand is healing and moving well. They may need to be seen for several years. Some children need another surgery to improve the function and appearance of their hand.

How we care for syndactyly at Boston Children’s Hospital

The Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Department’s Hand and Orthopedic Upper Extremity Program and our Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery’s Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery Program have treated thousands of babies and children with syndactyly and other hand problems. We are experienced treating conditions that range from routine to highly complex, and can provide your child with expert diagnosis, treatment, and care. We also offer the benefits of some of the most advanced clinical and scientific research in the world.

Our Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Department is nationally known as the preeminent center for the care of children and young adults with a wide range of developmental, congenital, neuromuscular, sports-related, traumatic, and post-traumatic problems of the musculoskeletal system.

Our Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery is one of the largest and most experienced pediatric plastic and oral surgery centers anywhere in the world. We provide comprehensive care and treatment for a wide variety of congenital and acquired conditions, including hand deformities.